"I began to turn the idea over

in my mind, and it began to coalesce into a possible novel. I thought it would

make a good one, if I could create a fictional town with enough prosaic reality

about it to offset the comic-book menace of a bunch of vampires."

--Stephen

King, On Becoming a Brand Name,

Adeline Magazine, 1980.

Edition:

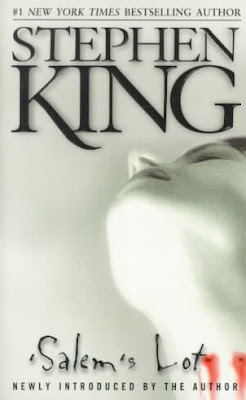

Simon & Schuster “Pocket Books Fiction” Mass-Market Paperback printed Nov.

1999; cover with the generic pasty-faced girl head tilted up all “kiss of the

vampire” like with the bleeding puncture wounds on neck.

A

word that pops to mind in discussing King’s writing is “inveterate.” His

process, as recorded in On Writing: A

Memoir of the Craft, is to type a daily word total of 2,000 words per day,

more or less ten pages. This type of methodical craftsman style is straight out

of the pulp tradition from which he was profoundly influenced, where the onus

was on quantity and not always on quality.

This

is important because by all accounts it’s what King stuck to even when he was

teaching public school kids—the nightmares—and living in a trailer in Harmon

and typing his stuff out on a kids writing desk in the mud room after the

school day. And it was in these conditions that he began work on a novel that

he describes as a “Vampires in Our

Town” (On Writing, King, p. 86)

To

me, personally, this amount of writing is simply astounding. I’ve tried to

write stuff after coming home from a full day’s work. It sucks. King himself

says it felt like “by most Friday afternoons I felt as if I’d spent the week

with jumper cables clamped to my brain” (On

Writing, King, 73), and to pound out any pages at all, much less a

thousand, and much less GOOD pages, requires a force of will that I don’t see

how anyone can deny as exemplary. And this is with the added bonuses of two

kids, in a trailer, with housework to be done and lesson plans to make…

Forget

about it.

Say

what you will about King—say he’s not a good writer, say he’s not worth of

literary consideration, say that he’s a hack, but you cannot deny the man’s

love for what he does. What kept him writing when the forces of the world were

practically compelling him not to is something that we should all aspire to

attain.

On

the heels of the hardback publishing of Carrie,

King’s new novel was inspired by the various monster comics and vampire based

stories he read when he was younger. He often relates a humorous tale of

discussing the project with his wife, Tabitha, wherein he wonders what would

happen if Dracula appeared today (that is, 1970s), not in a sleepy English

hamlet but in a bustling metropolis like New York. At some point, either

himself or Tabitha expostulated that the Prince of Darkness would probably just

get run over by a bus. But the spark grew from there, the setting changed

(importantly) to the American version of the sleepy hamlet town: the Idealized

Pastoral Vision of Americana, the small town blue collar folks that hold the

country together through integrity, kinsmanship, and kindness.

Ostensibly,

anyway.

That

initial conversation is telling, because Dracula’s

influence on the novel can hardly be ignored. Both books involve the subtle

deconstruction of ideals—Victorian sensibilities, esp. sexual, in Dracula, and small-town America in ‘Salem’s Lot--both have a team of people

who come together though a confluence of circumstance, both have a main female

character killed, turned, staked and tossed in a river, both have the same sort

of team dynamic—Ben Mears and Jimmy Cody outright say that Matt Burke reminds

them of Van Helsing—and of course both have the heroes defeating the big bad.

The biggest divergence in both novels structure is probably the ending—King

basically kills everyone and has the town be overrun, Stoker lets the good guys

have a relatively happy existence.

But

you can take it to mean that ‘Salem’s Lot

really is a sequel to Dracula,

not only in terms of subject matter but in terms of thematic relevance. The

boogeyman just got transplanted from Victorian England to small-town America,

and King updated the legend and what Dracula

signified for a modern audience:

"I

wrote 'Salem's Lot during the period when the Ervin committee was sitting. That

was also the period when we first learned of the Ellsberg break-in, the White

House tapes, the connection between Gordon Liddy and the CIA, the news of

enemies' lists, and other fearful intelligence. During the spring, summer and

fall of 1973, it seemed that the Federal Government had been involved in so

much subterfuge and so many covert operations that, like the bodies of the faceless

wetbacks that Juan Corona was convicted of slaughtering in California, the

horror would never end ... Every novel is to some extent an inadvertent

psychological portrait of the novelist, and I think that the unspeakable

obscenity in 'Salem's Lot has to do with my own disillusionment and consequent

fear for the future. In a way, it is more closely related to Invasion of the

Body Snatchers than it is to Dracula. The fear behind 'Salem's Lot seems to be

that the Government has invaded everybody."

Certainly

a U.S. 1970’s proposition if there ever was one. But King’s novel not only is

frightening in its sensibilities and subject: it terrifies on its very thematic

core, by way of the cultural hierarchy it seeks to deconstruct.

II.

The Town

The

Town has a sense, not of history, but of time...

--Salem’s Lot, p. 163.

Mom I love you but this trailer’s got to

go

I cannot grow old in Salem’s Lot

--Eminem, Lose Yourself

There are two ways to gain immortality

in the world of writing. The first is to be the voice of an age, write a novel

that perfectly captures the culture and attitudes of the epoch in which you are

a part. Catch 22, Infinite Jest, possibly even Shakespeare

falls under this head. These are works through which we can study history as

much as art, understand where we have come from and where the work is trying to

lead us.

The second way is to be timeless. Voices

of an age, while usually brilliant writers, can sometimes become trapped within

their own purview. They can become obsolete, and outdated. But timelessness

encompasses more: stripped down, the bare essence of the work leans on figures

and tropes as old as art itself, and just as durable. The Illiad, War and Peace, Lord of the Rings, titles like that.

Now these two designations are by no

means mutually exclusive. And I would wager, in fact, that the best works—the

ones that are truly nonpareil, that are recognized as shining examples of man’s

creativity—have elements of both. Certainly there are elements of timelessness

in Shakespeare, and certainly there are elements of the age in The Illiad, where Greeks fight for honor

and glory even facing the stark realities of brutish war.

I think Salem’s Lot falls into this category as well. It certain has that

timeless quality: it doesn’t really matter that the novel is purely a 70’s

piece, that the Vietnam War is the current news of the hour and that no one has

cell phones and that trailer parks are a relatively new oddity; these things,

which could have entrapped the novel, mean as little as the Victorian fringe

does to Dracula. Because deep down,

something in both novels speak to an enduring feeling in the human soul: of

fear, of façade, and disillusionment.

But that doesn’t mean Salem’s Lot can’t be studied in the

context of its environment; to be quite frank, if one asked me what is the best

novel to capture the zeitgeist of

American culture in the short years after the end of Vietnam and the beginning

of the wanton excess of the 80s, I would hazard that there are worse things to

recommend than Salem’s Lot, because

the novel encapsulates as well as an history book the post-Vietnam bitterness

that in part led to the metropolitan boom of the 80s. And that is the total and

complete destruction of the ideal of peaceful, small-town America.

“The blue collar folk,” as it were. A

charming figment that existed as long as America had, but its current form (or

current in the 70s anyway) stemmed from the post-WWII dream of escape to the

suburbs with the children, raising cute little families with the Norman

Rockwell Thanksgiving dinners. Small town America was the country’s bread and

butter. They were the innocent folks, the good folks, the simple and the kindly

folks untouched by the ravages of those menacing influences in New York or Los

Angeles or the world at large. The best that America had to offer in terms of

plain, simple goodness.

This idyllic photograph of the American

family and small town had begun to disintegrate pretty early in the 1960s, when

the civil rights movement brought to a national and global stage a whole other side to the simple kindly

country folks--who just happened to beat black people to death and pour salt

and milkshakes on them for daring to sit in a restaurant. This sort of sweeping

hatred had existed since time immemorial, but it was only here, at this

juncture, when the Civil Rights movement really took off, that the world

noticed. Taking into account the ravages of Vietnam, the scandals of Watergate,

the collapse of the image of America as a beacon of truth and light to the world,

and it’s no wonder that mistrust, paranoia, and darkness are central to the

core of Salem’s Lot.

King himself says that the theme is

indicative of the sense at the time that not only was the government in

everything but doing a pretty terrible job of dealing with it. And while it’s

undeniable this plays a part, I think it’s a bit too simplistic of an

understanding. Because while the invasive arms of the outside word coming to

destroy the simple, poor town of Salem’s

Lot is undeniably a heavily focused part of the plot, the novel makes it

perfectly clear that the rot was in the quiet town of Jerusalem’s Lot long

beforehand: “There’s little good in sedentary small towns,” says Matt Burke to

Ben Mears. “Mostly indifference spiced with an occasional vapid evil—or worse,

a conscious one” (186). All throughout the novel, there’s a sense of the town’s

death: not just by the obvious means of vampires, but by the very fact of the

world’s existence. It’s not apparent—in fact, it’s very subtle, but it is

there:

“It was in the

southwest area that the trailers had begun to move in, and everything that goes

with them, like an exurban asteroid belt: junked-out cars up on blacks, tire

swings hanging on frayed rope, glittering beer cans lying beside the roads…In

some cases the trailers were well-kept, but in most cases it seemed to be too

much trouble.” (39-40)

It’s easy to see in the frank

description of the lower-class inhabitants of the town the entire problem. The

trailers are seen as a cancer, a fact of life that’s invading the ideals. The

small-town America of yore is one of ice cream parlors and front porch swings,

not trailer parks with knee-high grass. Yet the trailers have moved in and seem

to be going nowhere. I don’t in any way think King is trying to denigrate people

who live in trailers—seeing as he himself spent a good part of his life in one,

I don’t see how he could—but this frank and almost aloof description says

everything we need to know about peaceful and innocent Salem’s Lot before we even get into the novel proper, our first

sign, if we’re paying attention, that while the great evil may be the vampires,

the selfishness and myopia of the town is what lets it arrive.

First

Section: The Lot (I)

The novel has four sections titled “The

Lot,” a stunningly appropriate number reflecting the seasons of the Lot through

the narrative. The first section—let’s call it spring—is all about beginnings.

School starting, Ben arriving and meeting Susan’s parents, the host of

characters to play parts in the novel are introduced, and the very start of the

chapter begins before dawn, before the awakening of life. Things progress, we

see the “normal” day of the Salem’s Lot civilians—and

some things decidedly un-normal. The sun rises on the world and life sort of

“begins” for the people who live there; it’s the same thing they’ve been doing

every day for years, certainly, but it is nonetheless and continuing cycle of

starting over; of revivification. It has its patterns and it has its expected

hills and valleys, even the more depressing aspects (e.g. school starting). The

only hint of danger is when Mike Ryerson discovers a dog hung upon the cemetery

gate—a discovery so out of the purview that it basically ruins the man’s day.

But other than that, it’s all setup.

It’s all beginnings. The good folk of the town—maybe a little rough around the

edges—getting up, going to work, leaving their secrets at home.

Second

Section: The Lot (II)

The second section is interesting.

Although it would ostensibly cover summer, it actually begins on the first day

of fall. The actual “summer” is barely mentioned in passing—hot days and

ninety-five degree temperatures in the mill—but then fall comes and “kick[s]

summer out on its treacherous ass as it always does one day sometime after the

midpoint of September, [staying] a while like an old friend that you have

missed” (193).

The entire elision of summer is

significant. Summer in the Lot is

described as a miserable, ingloriously hot time. But it’s still Summer. Life unblemished,

green everywhere, in the fullness of its cycle. Summer is a time of completion:

the birth and growth that has occurred in the Spring has reached its apex. It’s

a time for living—but not in Salem’s Lot, not now. Death has covered the

doorstep, and the townspeople welcome the Fall.

There’s an elegiac sense that many

people have about Autumn—the colors of the leaves, the cool, windy days.

Football season in America, Thanksgiving and fine weather. It seems like we’re

wont to forget what Autumn signals, even when we point it out: an ending. A

beginning of death. Things slowly die and we marvel at the beauty of it. It’s

called the “Fall” for more than one reason, and nowhere is that more applicable

than to Jerusalem’s Lot, where the fall is going to come quickly, unexpectedly,

and hard.

I think the language used here is simply

a nice touch: “an old friend that you have missed,” the fall is called. And in

this beginning of fall is the true invasion of the town begun; like an old

friend; or is this not the way the vampire seduces its prey? One only has to

look at how the fall is welcomed and how the Barlow approaches Dud in the dump

near the end of the same chapter: like an old friend, that he’s missed for a

long time. Someone to encourage him, someone to make him feel better: “…and

when the pain came, it was sweet as silver, as green as still water at dark

fathoms” (227).

The people of Salem’s Lot welcome the

fall as an old friend, desperate to escape the hearty vitality of the summer.

But they forget that fall leads to winter. They forget that fall has other

meanings. And in welcoming autumn, they inadvertently welcome the town’s fall

as well.

Third

Section: The Lot (III)

As the second section barely bypasses

summer by starting on the first day of fall, the third section details the Fall

in and fall of the town in all its macabre despair. The first line of the

chapter tells us everything we need to know about what’s going to occur:

“The

town knew about darkness” (312).

The chapter takes place right when

circumstances start to line up for the intrepid gang of fighters, when they

first begin to get a glimpse about what is infesting the town and the set-up

for their doomed fight against it.

The first section details a town in its

normality: there are crazy things that happen; a dog is found staked to a fence

and there’s a menace that keeps bothering the local real estate two-timer, and

of course people are mean and curse and are generally jerks to one another and

have dark secrets they don’t dare present to the public, but for the most part,

the first section details “normality”: farm work, schoolwork, bullying on the

playground, the daily ins-and-outs of a “normal” small-town existence.

The third section details the insane; a

caustic switch from accepted normality to unaccepted other, acts perpetrated

that are outside the shade society draws over the world. The bitterness of a

backbreaking, unrewarding life. A quiet man who killed his adulterous wife and

dropped her down a well and lived with it for twenty years. A young boy who

goes on to future wealth and success that started a fire that burned down half

the down, the guilt of which ushered him quicker into the grave. The local

fire-and-brimstone preacher dreaming of young girls naked and eager. The

hardware store owner that crossdresses out of sight of the wary eyes of the

town.

There’s an abrupt but fluid shift in

this section, where the mundane depravity of man turns into the supernatural

depravity. The hardware store owner, George Middler, and his sexual fetishes

are described, and then the novel smoothly transitions:

“or

that Carl Foreman tried to scream and was unable when Mike Ryerson began to

tremble coldly on the metal worktable…” (318)

There’s not tonal or syntactical shift

between the descriptions of unaccepted-other and supernatural other in the

section; it’s a subtle but apparent indication of what King’s trying to put

forth. The vampirism in Salem’s Lot is a new darkness, but for all its evil,

it’s simply an ancillary to other, deeper darknesses. There’s a standard trope

in American fiction, borne out of suspicion of the other: the trope where the

small town is corrupted by outside influences and turned into something that’s

not. But here King says that the town wasn’t corrupted by outside influences:

the town was already corrupted. Already teetering on the brink. Already about

to fall. The Outside Darkness doesn’t come in to destroy Salem’s Lot. The

Outside Darkness simply exposes what’s already there, and lets Salem’s Lot

destroys itself.

The

Fourth Section: The Lot (IV)

And all that’s left is the winter.

The first section detailed the

beginning, the birth, the spring. The second, detailed the (missing) summer,

banished for being too hot despite its fullness of life. The third detailed the

fall. And now the fourth, details the winter. Death and emptiness. As in the

third section, an early line in the chapter says everything we need to know:

“No one pronounced Jerusalem’s Lot dead on the morning of October 6; no one

knew it was.” The fall has occurred; the rest is simply cleanup.

The chapter titled The Lot (IV) is the second-to-last

section of the novel proper, before the short Ben and Mark section and the

epilogue, and it’s fitting. The novel’s a tale of disease and rot, after all,

and the town’s entered a winter from which it will never return. Most of the

chapter is divided between last ditch and more-and-more hopeless efforts to

save the town (including a deliciously malevolent letter from Barlow to the

protagonists), until even they realize there’s not hope. They best they can do

is take the head (Barlow) off, and leave the town to the minions.

If there was ever any real doubt about

the thematic implications of Salem’s Lot,

Parkins Gillespie puts them to rest near the end of this section and the novel

proper. Ben and Mark approach him to explain what’s going on and maybe enlist

his help, but Parkins is well-aware already, and says he’s skipping town:

Ben heard himself say remotely, “You

gutless creep. You cowardly piece of shit. This town is still alive and you’re

running out on it.”

“It ain’t alive,” Parkins said,

lighting his smoke with a wooden kitchen match. “That’s why he came here. It’s dead, like him. Has

been for twenty years or more. Whole country’s goin’ the samw way. Me and Nolly

went to a drive-in show up in Falmouth a couple of weeks ago, just before they

closed her down for the season. I seen more blood and killin’s in the first

Western than I seen both years in Korea. Kids was eatin’ popcorn and cheerin’

‘em on” (593).

And of course, he’s right; hindsight has

in no way proven otherwise. The dream of small-town America, that glorious

ideal made manifested in all its nostalgic glory post-World War II, but having

existed long before, had died out. The world had, and has, irrevocably changed;

and while some might say it’s for the better in many ways (which it is) it’s

King’s tone here that makes this

novel remarkably dissimilar of others in its genre. The tone alone separates

it. Certainly, King is doing the by-now rote plot of “pulling back the layers

of our society to expose the darkness beneath.” Plenty of people have done that

before, and more have done it since. But most novels of that ilk treat the

“peeling back” with something like glee, or vindication, or even satire; they

rub our noses in it and all our petty notions of good country folk and

hardworking people doing the 40 hour week to send it on down the line and say:

“Hey, it’s not so admirable after all!” What makes Salem’s Lot so interesting, to me anyway, is that’s not King’s tone

at all. For all its horror and all its insistence of the pervasive rot within

the false dream of small-town simple America, Salem’s Lot has the marks of an elegy, a sad wistfulness of truth.

By the end of the novel, basically the

whole town is vampiric, and those that aren’t are soon to follow. And so when

King says:

“[Ben] got behind the wheel and

started the engine. As he pulled out onto Railroad Street, delayed reaction

struck him like a physical blow, and he had to stifle a scream.

They were in the streets, the

walking dead” (612).

You have to wonder if he’s still talking

about vampires, or the small-town blue collar workers held up as the backbone

of America. King’s tone distinguishes Salem’s

Lot from other novels of its nature, redolent with an underlying

despondency; an acknowledgement that the dream of simple America doesn’t exist,

never has—but an aching sadness that it doesn’t.

Which is why the epilogue of the novel

is probably the most hopeful case of arson in the history of literature: “’But

they say fire purifies,’ Ben said reflectively. ‘Purification should count for

something, don’t you think?’” (630). Ben and Mark planned to try and burn the

town down, and perhaps most of its vampires along with it. The act contains a

sense of rebirth, of starting over. The end to the cold of winter, beaten back

by the heat of fire, the heat of renewal, the heat of spring. And so does the

novel end in the town as it began: with the spring coming. King, like most of

his compatriots of that era, may have been disenfranchised and disillusioned

about America and its place in the world. But as Salem’s Lot indicates, that doesn’t mean there can’t still be hope

of reclamation. (1)

|

| PICTURED: I'm sorry but...what... |

IV:

The Aftermath

Salem’s

Lot

remains one of King’s most famous and enduring works, a quintessential part of

the vampire canon, taking its place alongside its spiritual predecessor Dracula. Pragmatically, it was a big

hardback and paperback bestseller, and thunderously declared that King’s

presence was more than fleeting, more than a one-hit wonder, and more than the

luck of a great director adapting a first novel.

The novel remains one of my favorite’s

of King’s, even though upon a critical re-read it’s definitely the work of a

man trying to pay the bills and fine-tuning his craft. The flow of the novel is

sometimes clunky, things sometimes just happen one after the other in a

standard and flat plot progression—not unexpected, but not compelling either.

But the good far outweighs the bad, especially the sections where King

ruminates on the nature of small towns and the hidden darkness therein. He again

makes use of his high-mileage technique of journalistic showmanship, and again

in chilling fashion, esp. in the prologue, which sets upon an absolutely

profound sense of dread that gets the first time reader quivering by the time

the plot begins. Some bandy about the notion that King’s endings are

by-in-large weak (they certainly can be), but man-oh-man, no one can say the

same for his beginnings. He’s an absolute master of mystery—not the Raymond

Chandler kind of mystery, but the mystery of the unknown, well illustrated by

the Prologue to Salem’s Lot. He knows

how to build it, utilize it, and most importantly, let it fall to the wayside

before the reader gets impatient.

As for the ending—I personally think

King gets a bad rap for the overall quality of his endings. Certainly some are

better than others, and certainly many are weak. But there are those who act

like most of his output has terrible endings, and I don’t think that’s quite

the case. Salem’s Lot, for example,

has a great denouement and aftermath. The protagonists can’t be said to have

lost, but certainly can’t be said to have won—a more Pyrrhic victory you will

never find outside the annals of military history—which I think is very fitting

for what the novel’s trying to do and say. And the final pages of the epilogue

give the reader chills, leaving them with a question that cannot be answered

(2), a technique that doesn’t always work, but does in this case. We can’t be

sure that the fire will take out all the vampires, even Ben says so (3). But

there’s always the hope.

With King

established as a popular, well-regarded and (finally) financially secure

author, there was now a time for breathing. For rest, relaxation, and looking

back at success. For taking life easy and living for the moment and resting on

your laurels. Fortunately King did none of these things. Instead, he strove

higher, and his final third in the one-two-three punch his first novels

provided to popular culture saw the full culmination of both his style and

storytelling in what remains arguably his most enduring and well-regarded work.

Until next time,

Mr. E

(1)

And

of course this illustration is subsequently ruined by the canon story “One for

the Road” (collected in his first short story anthology Night Shift and afterwards in the Illustrated Edition of ‘Salem’s Lot) in which it becomes

apparent that not only did the vampires in the town not get all wiped out, but

are, in fact, thriving—which leads to horrific post-realizations about whether

or not Ben and Mark survived their final mission to end the vampire menace in

the town…

(2)

Again

ruined by “One for the Road”

(3)

Again

ruined by “One for the Road” (I suddenly feel the need to make it clear here that I

actually really like “One for the Road,” but there’s no denying that half my

post falls to pieces if I don’t blatantly disregard it.

This was an incredibly thorough look at "Salem's Lot". I really enjoyed your thoughts. I haven't read the "Night Shift" anthology, but now I really want to check it out. One of the things I love about King is how his canon is interwoven - probably one of the reasons I enjoyed the Gunslinger series so much.

ReplyDeleteBeing a vampire is not what it seems like. It’s a life full of good, and amazing things. We are as human as you are.. It’s not what you are that counts, but how you choose to be. Do you want a life full of interesting things? Do you want to have power and influence over others? To be charming and desirable? To have wealth, health, and longevity? contact the vampires creed today via email: Richvampirekindom@gmail.com

ReplyDelete