My relationship with Buffy: The Vampire Slayer is rather odd. I’ve liked the show for closing on thirteen or fourteen years now. I finished watching all the episodes just a couple of weeks ago. Contradiction? Not back in 1999, where bootlegging actually involved “legging” VHS tapes from friend to friend and DVD players were just being pronounced the greatest and final evolution of the home entertainment market (Note: There might be some slight exaggerations. –E).

I was about eight or nine when I very first saw

Buffy, in its nascent state as a mid-season replacement on the fledgling WB network, and as a young

child I hadn’t yet grasped the intricacies of either taping things on VHS or interpreting the time

management involved with watching serialized television shows. When I caught Buffy, it was a one

off episode here or there, maybe a marathon I stumbled upon. I didn’t become

extremely attached to it—and be advised that my memories of the period are

nebulous at best—but I do remember being unable to change the channel whenever

it was on. I didn’t quite get everything that was happening, but I knew there

were fight scenes, vampires, and some spine-tingling, smile-inducing moments

that I would later discover go by the name of “good writing.”

For whatever reason, I recall that most of the episodes I

did see were during season 2/3, though I do remember seeing the end of “The

Gift” and having no idea what in Glory’s name was happening—but that might have

been later.

See, as much as I liked Buffy,

it never really was on my radar more than just something that was interesting

on television if I happened to skip across it on a slow day. I was much more

into Dragonball Z at the time (and you were too, so zip it). Buffy didn’t

really transcend into a consistent interest until much later, after the series

had ended and reruns had started popping up everywhere.

I want to say it was on the CW where I first began to watch Buffy in earnest, and I want to say it

was around 2005 or 2006, but no later than 2007. But I spotted it on

whatever-channel-it-was on Saturday mornings, and after the obligatory

recognizance light went off, I made it a point to watch it. Every Saturday

morning, usually two episodes back to back (at first, anyway). The season most

salient? Six.

Dum--Dum--DAAAAA…..

To this day I feel that my leniency towards season six is

partially due to this juncture, watching it weekly while eating cereal

on a non-school day. I’m aware, now, of just how divisive six is—yet I can’t

summon up any great rage against it, and I think these Saturday mornings were

the reason why. Partly because of nostalgia glasses, sure, but partly because

I think I can look at six more objectively since I hadn’t had as

much investment into the Scooby Gang . Since I hadn’t

canonized their characters in mind, the “darkness” and “despondency” of six

never really annoyed me, and in fact I thought it was exceedingly well-played.

I remember vividly seeing the end of “Dead Things,” where Buffy learns, from

Tara, that she didn’t “come back wrong” and cries that she doesn’t want to be

forgiven. I also remember seeing parts of Grave and the entirety of

"Doublemeat Palace"—a fact that will come back to haunt this list

later.

For whatever reason, the Saturday morning thing dried up,

and I can’t remember specifically why. I think it was a combination of factors:

I started having to be places on Saturday mornings more often than not—work?

Football practice? And the fact that I think CW or whatever channel messed with

the lineup, showing one Buffy episode instead of two and then not showing them

at all in the mornings, or something. So that pipeline dried up, and Buffy once

again fell to the backburner as a show I remembered enjoying but never quite got

around in the pre-streaming world to finishing.

So imagine my jumping at the chance when I discovered

Netflix streamed not just part, not just most, but every single bit of Buffy: the Vampire Slayer? Finally, at long

last, I had a convenient and easy way to finish this remarkable series, and

accomplished in three months what I hadn’t been able to do for thirteen

years—follow it from episode one right on up to the end.

Now the question is—what to say about it?

I mean, you have to say something

if you have a blog. That’s practically a mandate: finish landmark

entertainment, blog something about it. At least that’s what I interpreted from

Bloggers’ Terms of Use. But what is there that can be said about Buffy: The Vampire Slayer that hasn’t

been said ad nauseum (and more

eloquently) before? Am I condemned to repeat what everybody already knows,

about how great the show is, the depths of the characters (and their salty

goodness), its sometimes heavy-handed but always earnest use of metaphor, the

doldrums of season 6, the unmitigated quality of season three, the shocking

turn in season two, the groundbreaking hours of television in season four,

five, and six (again); the outrageous elision by the Emmys and the heaps of

praise of which this series deserves every single letter?

What is there to say that’s not covered by the Buffy

conventions and the Buffy books of criticism of the Buffy fan sites and the

hundreds and thousands of blogs out there that mention Buffy and the Joss

Whedon critical companion?

And then it came to me: a top ten episode list! No one’s

ever done one of those before!

…

…

II: A (Slightly) Different Take On the Top Ten List

I’ve mentioned before the difference between “objective

quality” and “favoritism,” and how it’s hard to separate the two within our

minds. Someone’s “favorite” whatever can be influence by a number of factors:

nostalgia, circumstances in life, the characters involved, etc. I

loved and still love Dragonball Z—even though it obviously has severe weaknesses, even in its unaltered

Japanese incarnation.

So that being said, this is a top ten favorite episode list, not necessarily the best episode list. Objective quality is hard to gauge even at the best

of times, and I have no real desire to delve into that minefield just now (although I probably should put what I think are the top ten best episodes in footnote--oh wait, there it is: (1)).

Now, top ten episode lists are about as rare as corn in

Iowa, and that holds even more true

in regards to Buffy. How, I can practically hear you asking,

can the indomitable Mr. E craft an even minutley-unique perspective on a top ten

list? Why, by making a top ten list that’s not about the top ten episodes!!!

…

…

Okay, this is proving a bit more tortuous than I thought.

Let me put it this way: objective quality, despite hot

debate, tends to rise to the surface, like delicious cream, and in the

Buffyverse, there is a pretty well-understood census of agreement as to which

are the best and favorite episodes.

After having trawled the ENTIRE INTERNET (well, maybe the first five pages of

Google) for Buffy top ten episode lists, for the most part said lists will

consist of 10-20 of the following episodes, in no particular order:

- Restless

- The Body

- Once More, With Feeling

- Hush

- Becoming (1 and 2 combined)

- Graduation Day (1 and 2 combined)

- New Moon Rising

- The Gift

- Passion

- Surprise/Innocence

- Conversations with Dead People

- The Prom

- Earshot

- Prophecy Girl

- The Wish

- Who Are You?

- The Zeppo

- Chosen

- Grave

- Doppelgangland

- I Only Have Eyes For You

- Normal Again

- Fool For Love

The order might be different, and an odd episode or two

might pop up, but generally these are the eps that make the list—including

mine.

Which is why I wanted to take a different tack. Because,

like my fellow bloggers, fact is if I were to make an out and out top ten

favorite episode list right now, it would look something like this (again, no particular order):

- Hush

- Restless

- Amends (more on this in a moment)

- Surprise/Innocence

- Graduation Day

Five by FiveThis Year's Girl (Note: Embarrassing mistake noted by a shrewd commenter. --E) /Who Are You- Passion

- Becoming (1 and 2)

- The Zeppo

- The Body

And then I would write a small paragraph about them,

basically saying the exact same things everyone else has already said, more

often than not better than I could.

So I decided not to do that.

Instead, I’m going to make a different sort of top ten list.

One of the lesser eps. The forgotten ones. The “out of the way” episodes that

you rarely replay on your DVD player unless you’re trying to watch the entire

series over again.

You can call this “favorite episodes 21-30,” if you want. Or

the bad ones I liked the most. Or something. And yes, I’m sure a few of these episodes

have, at one point or another, popped up on a top-ten list somewhere—I’m almost

certain that every Buffy episode is

on someone’s top ten list. But these

don’t make the cut all the often.

Some of them are legitimately good episodes that just didn’t

reach the highest tier. And a couple are episodes that most of the fandom

regards as forgettable to mediocre to outright bad, but that, for whatever

reason, appealed to me. But remember: this is not a list of objectivity, but

subjectivity. These are favorite episodes that I am well-aware of the

weaknesses of, or strengths of. But I think most Buffy episodes deserve at

least some praise, even the truly terrible ones, and so here’s a little nod to

a couple of them:

III. My Top Ten "Off-the-Beaten-Path" Episodes of Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

Honorable Mention: Season 3, Episode 10, "Amends"

It’s probably bad form to start off a top ten list with specifically delineated goals with something of a cheat. "Amends," by no means, is an “out of the way” episode. In fact, it’s rather famous. Or rather, infamous. Which is why I included it here.

Honestly, I had no idea this episode was so divisive, and I

didn’t discover it until this blog on the Great Buffy Rewatch (which

everyone should check out) that I read while doing research for this list. As

it happens, "Amends" is apparently highly

controversial, from its vague baddy to its final conversation to its

quite-obviously-a-miracle that occurs at the end. And I was absolutely astonished

by this, because I didn’t see how anyone couldn’t just fall in love with this

episode. I know I did.

I’m a sucker for two—well, for lots of things, but two of

them are: sappy romance and divine intervention (if used well). "Amends" covers

this latter portion, and in my opinion, is used very, very well. The entire episode is about a force of nature trying to

convince Angel he has no place in the world and so should give in to evil—that

as it is, how else could the episode end without a resounding reminder that

Angel does have a place in the world?

Yes, it’s a deus ex machina, but

remember, deus ex machina is just a function of storytelling, and can be used as well or as badly

as any other function of storytelling. In this case, it’s used in a

subtle way, and fits with the episode perfectly: the white purity of the snow

itself, compounding with the visual idealism of Christmas, and the follow through on the implication that snow was the last thing expected to occur on a hot Southern California holiday.

But really, my overarching love for this episode down to the

Conversation. You know the one. Some call it melodramatic. I call it

gut-wrenching, and personally I think it’s some of Whedon’s best dialogue,

perfectly captured by some of Sarah Michelle Gellar’s and David Boreanaz’s best acting.

I get chills every single time Angel grabs up Buffy from where she lays on

the ground and desperately pleads: “Am I

a thing worth saving? Am I a righteous man?”

Or the insinuation that “It’s not the monster than needs killing in [Angel], it’s the man,” a wonderful and thought-provoking epiphany.

And hey, at the very least, the episode more or less sets up

the entirety of Angel: The Series, not to mention the Big Bad for season 7…though the latter may not be a point in its favor.

Number 10: Season Six, Episode 12 "Doublemeat Palace"

So let’s start off the list proper with some decent size controversy: I. Love. "Doublemeat Palace."

Remember (and I hope you do, because it was just a few paragraphs ago) when I said there’s a difference between objectivity and favoritism? My number 10 pick is pretty much the encapsulation of that. The fandom hates "Doublemeat Palace" (for the most part). And, objectively, I can see why. It’s depressing, it’s by and large pointless, its plot is oft-tread ground (hey guys, did you know fast food restaurants appear a bit sketchy sometimes?), and there’s the Ugh! bit where Buffy sneaks off between a double shift for a wall-grinding ugly-bumping with Spike.

But dang it, I can’t help it. I love this episode.

Maybe it’s nostalgia: remember when I said above how seeing "Doublemeat Palace" when I was younger

would haunt this list? Behold, the shoe dropping. I can’t help but have

some lasting affection for this episode I saw as a young scamp in the carefree

days of high school. It brings me to back to adolescence.

Or maybe partly, it’s because I worked fast food, and not only that,

but I worked fast food in Buffy’s situation: someone with at least some

college education, who could probably do better, but is stuck there because of

circumstances beyond her control. And while a lot in "Doublemeat Palace" is (understandably) exaggerated—a lot of

it hits home for me as well, right up to not quite knowing what’s actually

integrated into the products being served.

And partly, it’s the old lady: What about the cherry pieeeeee!?

So yeah, I love Doublemeat

Palace in all its glorious mediocrity, from its one the nose portrayal of

lifers in the fast food industry to the stupid cow-based uniforms to the Alien

rip-off phallic shaped bad guy—or snake, or whatever—I simply love. I’m sorry.

Please don’t kill me.

Number 9: Season 2, Episode 1, "When She Was Bad"

The general consensus is that while Buffy showed some sparks of quality right from the beginning, and signs that it could become something transcendent, it didn’t really hit its stride until the middle of season 2—with the Surprise/Innocence whammy. A fair assertion.

It’s obvious that the writers were in uncharted

territory, and it took them a while to figure out both the tone and intent

of the show. Whedon and Co. should be given props just for attempting some of

the insanity they were trying to put on screen. If there was anything that

could characterize the entire Buffyverse, it was courage, and a penchant for

pushing past the false starts—like giant praying mantis bug ladies.

“When She Was Bad,” gets sort of lost in the

shuffle. It’s not considered a bad episode, just not a particularly great one.

It comes in the up-and-down first half of season two (before the infamy) and

deals with Buffy attempting to bury the trauma she’s undergone at the hands of

the Master—you know, dying and all that jazz.

I personally think this is a really good episode. Whedon’s

always been good as digging into psychological trauma and expressing it in a

believable fashion—even Buffy’s catatonia from the end of season five made

sense in context—and “When She Was Bad” does an admirable job portraying a

young girl that represses a traumatic event by building a wall of distance and

egomania. The Buffy of “When She Was Bad” is nothing if not foreshadowing her

constant—throughout the series—need to be reminded that she not only can’t

handle everything on her own, but doesn’t have to, a motif that comes full

circle in the series finale, a whole five years later (man, do I love Whedon’s

ability to synchronize serialized television!).

Plus, it features a sexy Sarah Michele Gellar doing a sexy

dance with Xander set to some sexy music.

What’s not to love?

What’s not to love?

Number 8: Season 1, Episode 7 "Angel"

This is purely a personal opinion of mine (although I don’t think it’s an opinion that’s overwhelmingly rare): I love sappy romances. Call it a guilty pleasure. It’s one of the many anathemas of English majordom—you can’t have a good relationship anywhere in literature because it’s not angsty enough—but I can’t help it. Yes, sappy romance can be done badly. It can very easily be done badly. In fact, more often than not, it’s done badly. But Buffy provides one of the rare exceptions. Is it perfect? Well, no; honestly, I don’t know if sappy romance can ever be done perfectly…but it gets the job done.

Any story can be well done. Really. All it takes is the

proper consideration. And the relationship between Buffy and Angel is, quite

literally, Twilight if Twilight was competently written. To

wit: we have a much older, mysterious and very pale vampire (though he doesn’t

sparkle) going after a young, underage girl to the point where the word

“stalking” might be apropos. Underage girl, however, sees this not as creepy,

but adorable, and the two start a whirlwind romance with lots of angst and

drama.

It's essentially same story. The only

difference is the writing. When you have a 244 year old vampire and a 16 year

old girl, it's hard work to make it even a little bit un-creepy, and the fact

that Buffy succeeds at all in doing so is a true testament to the talent

of the staff.

Because their relationship is creepy at its most basic. But

that consideration is stymied by a host of factors: the obvious caring the

Angel has for her, the knowledge that Buffy's self-reliant and, in fact,

rescues Angel on a regular basis, and of course the performances from Boreanaz

and Gellar to make the whole thing not only seem believable but also seem like

the most natural thing in the world: of course

these two would be together!

Angel is probably

the most Twilight-ish part of the entire romance, what with Angel hanging

around Buffy’s house shirtless and sleeping in her room even though they barely know each other and what not, and

that’s without mentioning the terrible season one “sound-track” that evokes

charming images of the worst sort of overacted soap operas. But it also has one

of my favorite scenes in Buffy, where Buffy confronts Angel (whom she now thinks

she has to slay) in the Bronze.

David Boreanaz’s season one performance was stiff, to put it

kindly, but I think here’s a moment where we see a glimpse of the ability

that he actually has, as well as one of my favorite bits of dialogue:

BUFFY: You play me like a fool.

Come into my home. And then you attack my family . . .

ANGEL: Why not? I killed mine. I

killed their friends, and their friends' children. For a hundred years I

offered an ugly death to everyone I met. And I did it with a song in my heart.

BUFFY: A hundred years.

ANGEL: And then I made an error of

judgment. Fed on a girl about your age. Beautiful. Dumb as a post, but a

favorite among her clan.

BUFFY: Her clan?

ANGEL: The Romani--Gypsies. It was

just before the turn of the century. The elders conjured the perfect punishment

for me. They restored my soul.

Boreanaz, for all his weakness during this season, pulls off an interesting bit of menace here, a hazy toeing the line between

a good/ensouled person evoking the cruelty he was such a willing participant

in.

Of course this becomes a fight scene between Buffy/Angel and

Darla that encapsulates everything wrong with the direction and budgeting of

season one, including the way Julie Benz holds those akimbo pistols (bothers me

every time) and the fact that they seem to have bottomless magazines, and since

I’m not seeing a Solid Snake Infinite Ammo bandana on her person, I’m just

going to assume it was something the writers didn’t want to deal with—but you know what, that's okay. Because the ending of this episode more than makes up for it, in one beautiful visual encapsulating the entire relationship these two characters will have.

The point of Angel is illuminated in its title, and as a sappy romance fan I have no choice but to heap showers of praise.

The point of Angel is illuminated in its title, and as a sappy romance fan I have no choice but to heap showers of praise.

Number 7: Season 4, Episode 8: "Pangs"

Put on your helmets, kiddies, because I’m about to blow your mind: season four is probably my favorite season after the biggies (i.e., 2 and 3). It’s regarded as forgettable by a large majority of the fan base and outright loathed by a not-insignificant portion, but I’ve never quite understood why.

I think timing has a lot to do with the way Buffy’s

received. I’ve already recounted how I’m favorably inclined towards season 6

more because I wasn’t carrying the expectations of the previous seasons with me

when I saw most of it. To take that a step further, I think when you 're first exposed to the

Buffyverse makes a huge difference in how well you regarded certain seasons.

You start watching as a youngster, and the high school stuff is what relates to

you more, and when they get to college there’s a sort of distancing. You start

watching as an adult, and season six doesn’t bother you near as much because

you totally get the adult issues that the characters are going through. So as a

relatively recent college graduate, I’ve never minded season four. Yes, Adam is

a little bland—but to counterbalance, I don’t mind Riley at all. Four contains two

of my favorite episodes (“Hush” and “Restless”) and some of my favorite individual

moments, and is really the last time Buffy felt completely like Buffy to me for a sustained period of time, i.e. the whole season. Season five was really good and had some great

episodes, but also marked Buffy’s start into the adult drama

that characterized the latter half of the series. There’s no

compelling season long arc in four, and the Initiative is a pretty weak

exercise, but I never minded that. The fact that there are so many standalone

episodes might keep the season as a whole from being as compelling, but it also

makes it much more re-watchable, and that leads us to “Out-of-the-way” episode

number 7.

"Pangs" fits perfectly into a list like this because the episode really stands on its last fifteen minutes. Without them,

“Pangs” might just qualify as one of the worst episodes in the entire series.

I see what they were going for—taking the metaphors used in the “high

school years” into college, where one is more likely to be exposed to such

perspectives of how the Indians (We call

them Native Americans, Giles) were the victims of mass genocide in America’s

plans of “manifest destiny,” and all that—but the metaphor is about as subtle

as a scalping and basically boils down to Willow spouting off progressive

dialogues. The villains aren’t very interesting and Angel’s appearances—and

hiding from Buffy for a very weak reason—also count against it.

And then there’s the final fifteen minutes.

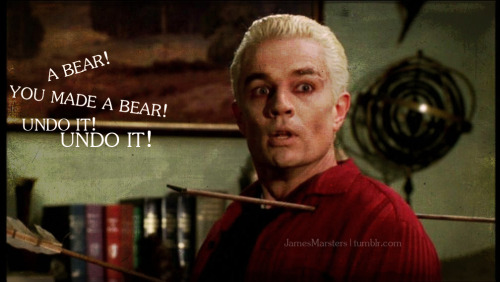

Honest to God, there might be no funnier bit of action in

Buffy: The Vampire Slayer than the last act of "Pangs." Everything from

“pincushion Spike” to the expressions of the cast at the end of the episode when Xander

lets it slip that Angel was in town (setting up the wonderful Angel ep “I Will

Remember You”) is laugh out loud hilarity. Some might think it’s a little too

slapstick. For me, it’s what Buffy is all about, the self-aware silliness, and

really—correct me if I’m wrong—but I don’t think there’s another episode like

this, pure, unadulterated goofing off—after season four—until season 7’s “Him.”

Buffy’s insistence on creating the perfect dinner is rote

but still an effective Thanksgiving barrel of laughs, especially in her

conversations with Giles, who still has trouble not calling his bubbly group of

teenagers “Bloody Colonials.”

And speaking of season seven…

Number 6: Season Seven, Episode Seven, "Him"

I want to make it perfectly clear that I don’t think any season of Buffy: The Vampire Slayer is “bad.” I will say that a few seasons of Buffy: The Vampire Slayer are weak. And to my mind, the weakest of all seasons was numero seven. It wasn’t as oppressively dark as season sex—er, I mean six—and it wasn’t as cheap-looking and ill-defined as season one, but of all Buffy’s seasons, it’s simply the least interesting. The episodes blur together, and not in the good the-arc-is-so-awesome-it’s-hard-to-separate season three way, but in the bad there’s just nothing memorable there kind of way. It wasn’t silly enough to be lighthearted nor dark enough to be oppressive. It was just sort of…there.

That’s not to say it’s bad. I quite enjoyed season seven; however

if some vengeful god-spirit came to me and said that to save the universe one

season of Buffy the Vampire Slayer

would have to be excised from existence forever, I would say seven with

little hesitation. Other than "Conversations

with Dead People," there was not a single episode that made me stand up and

go “Wow!” Even the oft-lauded “Storyteller” felt too bogged down by what was

happening at that point (Note to self:

May have to make later post entirely about season seven. –E).

As such, I feel rather confident in saying that “Him” is the

last true injection of lighthearted levity (Note to self: fairly certain that's redundant. --E) into the Buffy: The Vampire Slayer canon, and for a season as depressingly

contorted as seven, it’s something I’m very grateful for.

But Mr. E, I hear the three people reading this in a remote

scientific research center in Antarctica screaming. “Him” isn’t a good episode!

It’s just a less clever version of “Bewitched, Bothered, and Bewildered”!

To that I say: I completely agree. “Bewitched, Bothered and

Bewildered” is the vastly superior episode, and the two have more than a few

things in common.

Still, that doesn’t mean “Him” is completely unworthy and

totally devoid of its own unique wit. Sure, the love spell thing has been

well-covered ground, but “Him” also provides the series’ last-gasp of

magic/demon-as-metaphor that the show was so good at in the early seasons, with

its spin on the cliché of the jock with the letterman’s jacket having some sort

of insidious influence on the teenage girls surrounding him.

“Him” also had the distinction of having one of the most

hilarious moments in series, with a four-way tracking of Buffy, Willow, Anya and

Dawn as they each do their own thing in regards to making R.J. theirs, the best

of these being, of course, Buffy trying to kill Principal Wood with the rocket

launcher from “Innocence," all in a background montage that has Spike wrestling

the device away from her. Not to mention Spike and Xander’s grand “plan” of

getting the jacket from R.J., which involves running up to him and yanking it

away before he knows what’s happening.

I think part of my fondness for "Him" can be attributed to

this last-gasp sensibility. As great as “Conversations with Dead People” was,

it set the stage for the rest of the season, including the potentials, the ruin

of Giles and Buffy’s relationship, Buffy’s megalomania, all of it—meaning in a

certain way, “Him” is all the last pure distillation of

Buffy, with the high school metaphors and Buffy actually being happy and the

general fun of the story; doesn’t make it great, doesn’t make it any less of a

“Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered” rehash, but it does make me appreciate it more than it would otherwise.

Holy Dostoyevsky, did this post expand longer than I thought

it would! It’s official people, I’m going to have to split it up. So tune in

next time for my top five favorite “Out-of-the-way” episodes of Buffy: The Vampire Slayer!

(Note/Edit: Part 2 is complete! Read it here.)

(Note/Edit: Part 2 is complete! Read it here.)

Until then,

Mr. E

(1) If I was going to put a list of what are the objectively best episodes, it would look as follows:

1. The Body

2. Hush

3. Once More, With Feeling

4. Restless

5. The Gift

6. Becoming (1 and 2)

7. Surprise/Innocence

8. The Zeppo

9. The Wish

10. Passion

|

| PICTURED: An absolutely ecstatic Joss Whedon |

(1) If I was going to put a list of what are the objectively best episodes, it would look as follows:

1. The Body

2. Hush

3. Once More, With Feeling

4. Restless

5. The Gift

6. Becoming (1 and 2)

7. Surprise/Innocence

8. The Zeppo

9. The Wish

10. Passion